Internet age verification will have an effect, but not the one its supporters think

'We're going to make it slightly harder for young people to access social media, no matter how much mass-surveillance we need to do it!'

God sees what you’re doing on your computer.

Here we go again. The idea of mandating age verification for online porn is back on Australia’s policy agenda, championed by eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant, who proposed a pilot program back in March 2023. Since April 2024, it’s gained bipartisan support — which is incredible, because it’s a spectacularly stupid idea.

How did we get here?

The political alignment on this issue isn’t surprising if you think about it. The conservative Liberal Party’s support is predictable – they’ve never met a moral panic they didn’t like. Labor sees its role as being your parent, not your government, and the left has never been great at defending individual liberty. That was traditionally the domain of moderate Liberals, but they’re practically extinct thanks to Scott Morrison and the 2022 electoral bloodbath.

But why now? Why is the entire Australian political class suddenly convinced that internet age-verification is the silver bullet we need?

A solution in search of a problem

Supporters point to domestic violence as one justification. But the data tells a complicated story.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has reported an increase in sexual assault reports in recent years. In 2023, there were 36,318 victim-survivors of sexual assault recorded by police — an 11% increase from the previous year.

This marks the 12th straight annual rise in recorded sexual assaults.

The rate of recorded sexual assault victim-survivors increased from 126 per 100,000 people in 2022 to 136 per 100,000 people in 2023, the highest rate in the ABS’s 31-year dataset.

Regarding intimate partner violence, the Personal Safety Survey (PSS) conducted by the ABS shows a different trend:

- Between 2016 and 2021-22, the proportion of women who experienced partner violence in the 12 months before the survey decreased from 1.7 per cent to 0.9 per cent;

- There was also a decrease in the proportion of women who experienced violence by any intimate partner (including current or previous boyfriend, girlfriend, and date) from 2.3 per cent in 2016 to 1.5 per cent in 2021-22.

These statistics suggest that while reported sexual assaults have been increasing, the overall rates of intimate partner violence experienced by women have actually decreased in recent years, according to survey data. It’s the latter you tend to think about when you think ‘domestic violence’, because the former captures assaults by people the victim doesn’t know, as well as assaults by those who are known to the victim.

The apparent contradiction could be down to noisy data – we’re dealing with relatively small numbers that can show big percentage swings. Increased reporting could be due to factors such as greater awareness, improved support services, or changes in societal attitudes towards reporting such crimes.

But the takeaway here that’s worth keeping in mind in the context of this debate is that, according to Australia’s statistical agency, partner violence has fallen by almost half in five years. That is a huge drop, almost unheard-of.

So that cannot possibly be what is causing the sudden enthusiasm for internet age verification, right?

We’ve been here before (and it never works)

If this feels like déjà vu, that’s because it is. Back in 2007, Labor went to the federal election promising an internet filter at the ISP level. Their plan included a secret blacklist of banned websites that would simply return a “connection refused” error. The list was meant to block inappropriate content – everything from child abuse material to… graffiti?

Newspapers noted at the time that around half the websites on the blacklist were entirely unrelated to child pornography. From The Conversation:

The alleged blacklist also contained legal content, including Wikipedia pages, YouTube links, and even the website of a Queensland dentist. This lent weight to fears the filter would block more than just illegal websites.

This wasn’t a new idea even then. In 2003, Clive Hamilton co-authored a report about youth and pornography in Australia, famously declaring that “the information superhighway is principally a conduit for pornography.” The Australian Christian Lobby jumped on board, with their managing director Jim Wallace pushing for mandatory blocking of adult content in 2009.

(They actually thought Labor’s blacklist didn’t go far enough. More Wikipedia blocking might have got them over the line, though.)

But here’s the thing: every attempt to regulate the internet this way has failed spectacularly. Remember China’s Green Dam Youth Escort software in 2009? It was supposed to protect young people from inappropriate content but ended up being a privacy nightmare that also blocked images of cats and banned references to Garfield (yes, really – the software confused flesh-tones with orange fur).

The UK’s Online Safety Bill has been stuck in implementation hell since 2019, with tech experts pointing out that its age verification requirements are simultaneously too strict to be practical and too weak to be effective.

These failures aren’t bugs – they’re features. The internet was designed to route around censorship, treating it as damage. When you try to build walls in cyberspace, the data doesn’t politely queue up at customs – it finds another way through. People who lived through the peer-to-peer revolution of the 2000s remember this lesson well: for every Napster that got shut down, five more services popped up in its place.

The devil in the details (and there are a lot of devils)

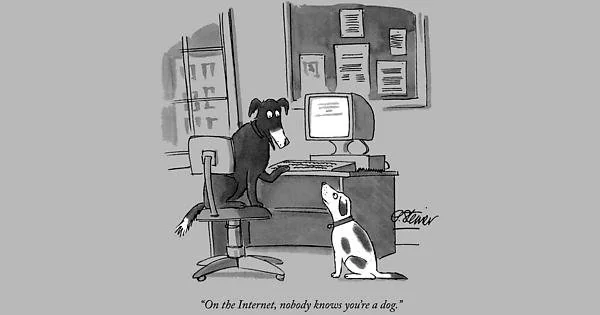

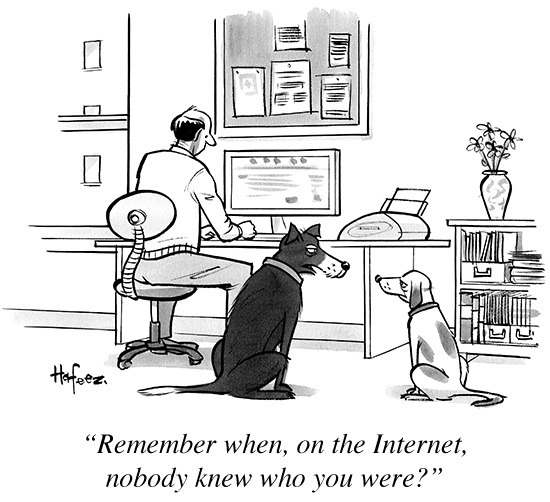

Remember that old internet meme, “on the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog”?

Well, under an age verification system, EVERYBODY would need to prove they’re not a dog (or underage). This means every Australian, regardless of age, would need to register with the government to access certain online content. But that’s just the beginning of our problems.

Here’s how it would likely work:

- Porn websites would need to register as official distributors of adult content

- Users would need to register for access rights

- The government would need to verify both parties and authenticate every access attempt in real-time

Sounds simple enough on paper. But let’s think through the implications:

First, there’s the “Streisand Effect” problem.

The Streisand Effect occurs when attempts to hide information backfire, causing it to spread more widely.

The term was coined in 2005 after Barbra Streisand’s failed 2003 lawsuit to remove an aerial photo of her Malibu home from a coastal erosion documentation project.

Before the lawsuit, six people had downloaded the photo.

After, 420,000 visited the site.

The term was coined in 2005 by Mike Masnick, highlighting how censorship attempts often amplify the very information they aim to suppress.

You can see how that would be especially applicable here.

Tell a teenager something’s forbidden, and you’ve just made it irresistible. Age verification would effectively create a government-certified list of “forbidden” websites. It’s like putting up a giant sign saying “Don’t open this door!” – you’re basically creating a recommendation engine for curious kids.

Then there’s the technical nightmare. VPNs already make up 30% of Australia’s internet traffic. Add age verification, and watch that number skyrocket. But it gets better: imagine the government trying to define what counts as “adult content.” Is an art history website showing Renaissance nudes porn? What about medical websites? Sex education resources? Wikipedia articles about reproduction? Anyone who’s ever dealt with content filtering knows it’s either too restrictive or too permissive – there’s no sweet spot.

The privacy implications are even worse. Every time you visit a restricted site, you’re creating a record. Even if the government promises they’re not keeping logs (spoiler: they will), the verification process itself leaves digital breadcrumbs. It’s like having to show ID at a bookstore, except the bookstore knows exactly which pages you read and for how long.

And here’s the kicker: the system would need to be “hack-proof” (nothing is hack-proof) because the database of verified users would be a gold mine for blackmailers. Imagine a data breach exposing not just that you visited adult websites, but exactly which ones and when. The Ashley Madison hack would look like a minor incident in comparison.

The cost? Astronomical. Every website serving Australian users would need to implement this system. Small sites would simply block Australian IPs rather than deal with the headache. Larger sites might comply, but guess who’s paying for all this infrastructure? That’s right – Australian consumers, through higher prices and reduced services.

In other words, to access adult content online, you’d need both advance registration and real-time government approval, all while pretending that this massive surveillance apparatus isn’t ripe for abuse, malfunction, or breach. Who’s going to sign up for that? Nobody – which is probably the point.

A simpler solution

Peter Violaris, head of global privacy at IDVerse (an age verification service provider), told the ABC:

“The point of the law, in my mind, is to stop young children, primary-school-age children accessing pornography on their smartphones in the playground. That’s a problem that no modern society should accept.”

He’s right about one thing – it is a problem.

The question isn’t if it’s a problem, but if this is the solution to the problem. Because that one is harder to say for sure. This solution is untested, costly, dangerous, and potentially unnecessary. It’s also ineffective, if it can be avoided without even trying.

(I’d agree that for those sites that need you to have an account to access them, it’s easier to enforce. You can limit access at the point of account registration, rather than browsing. But what kind of site has this requirement? Do adult sites require you to have an account? Of course not.)

I’m not the first to suggest that focusing on parental controls and education may be more effective in protecting children online without infringing on adult privacy. Emphasizing digital literacy and responsible internet use could address the issue without the complexities and risks associated with mandatory age verification.

Plus, it’s easier to do. These kids are going to be adults one day, and they will be immediately exposed to a world online that is suddenly open to them, without restrictions. Don’t we want them learning how to navigate that responsibly, before they’re given the chance to navigate it irresponsibly?

But here’s a radical thought: instead of creating a massive surveillance system affecting every Australian adult, why not address the actual issue? You know, the issue troubling Peter Violaris so much that he’s prepared to speak to the national broadcaster in support of a service that, wouldn’t you know it, his company sells.

If we’re worried about primary school kids accessing inappropriate content on phones, we could simply ban giving phones to children under a certain age. Make it illegal to supply phones with internet access to young children.

At least that way, we’d be targeting the specific problem instead of requiring 100% of the country to surrender their privacy to catch a few edge cases. But I suspect that’s not really what this is about.

Comments are for subscribers only